CHHATH AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL MEMORY OF HUMAN CIVILIZATION

-Chhath is not just a traditional festival; it is a wonderful language of communication between man and nature, in which faith, discipline, and beauty coexist. Amidst the speed, stress, and forgetfulness of the modern age, this festival teaches us to slow down, pause, and connect with the sun within us. Today, when science has captured the sun's energy through calculations and laboratory formulas, people still worship it as the god of light. This is the paradox that keeps faith alive amidst modernity.

CHHATH AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL MEMORY OF HUMAN CIVILIZATION

30-OCT-ENG 42

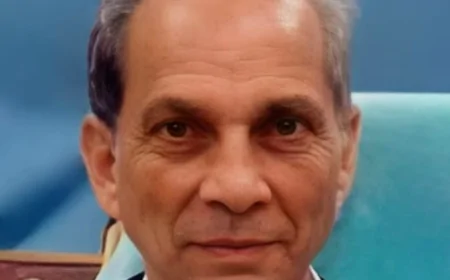

RAJIV NAYAN AGRAWAL

ARA--------------------------Chhath is not just a traditional festival; it is a wonderful language of communication between man and nature, in which faith, discipline, and beauty coexist. Amidst the speed, stress, and forgetfulness of the modern age, this festival teaches us to slow down, pause, and connect with the sun within us. Today, when science has captured the sun's energy through calculations and laboratory formulas, people still worship it as the god of light. This is the paradox that keeps faith alive amidst modernity.

Contemporary Western thought has viewed humanity's relationship to nature in technical and utilitarian terms. Since the industrial age, humans have recognized the sun as a source of energy, but Bhojpuri people have understood it as the soul. When solar energy was called "sustainable energy" in the West, women of Bihar and Purvanchal have been offering prayers to the sun for centuries, considering it the basis for the balance of body and soul. Science and folk beliefs are not in conflict here, but in a deep integration.

The silence of the Chhath prayer is the most intense state of modern meditation. The women standing in the water don't just gaze at the sun; they listen to the vibrations within themselves. It's a profound psychological moment where body, mind, and nature merge into one another. Western psychologist Carl Jung said that every culture has a shared image of the collective unconscious. The sun is its oldest, most radiant figure. Chhath's Surya Arghya brings to life that same primal symbol—an image of the light within humanity.

When the red glow of the setting sun spreads over the ghats on a Kartik evening, it seems as if the boundaries between nature and humanity have vanished. This scene lacks any grandeur, yet it is the most profound experience. Thousands of women, standing in the water, are engaged in a collective meditation in that moment. This experience is akin to modern psychology's "collective mindfulness"—a collective peace in which each person leaves behind their personal suffering and merges into a broader consciousness.

In modern society, where the individual is increasingly disconnected—from time, from community, and from his own body—Chhath reconnects him. The Western philosopher Heidegger stated that human existence is "Being-in-the-world"—meaning that human existence is not just within oneself but with the world. Chhath is a celebration of this "being-with." When a person stands in water and gazes at the sun, they transcend the limitations of their existence and become one with the universe. This is not a religious experience, but an experience of existence.

Contemporary science has proven that Surya Pooja is not only spiritually beneficial but also physically beneficial. The sun's rays produce vitamin D in the body, which provides relief from psychosis, depression, and fatigue. The discipline observed during Chhath's fasting and meditation detoxifies the body and stabilizes the mind. In this sense, Chhath is a process of psycho-somatic healing—where both mind and body are purified simultaneously.

When Western civilization divided life into pleasure and consumption, Chhath offered a middle path between restraint and beauty. This festival is neither a mere austerity nor a celebration. It combines both sacrifice and joy, and this is the greatest need of contemporary humanity—a balance that involves neither excessive sacrifice nor excessive consumption. The spiritual practice practiced during the four days of Chhath refocuses the soul lost in the hustle and bustle of modern life.

In today's world, environmental issues are often merely a matter of policy or research, whereas Chhath transforms them into a life practice. The purity of water, the worship of the sun, the cleanliness of air and soil—these are all symbols of ecological consciousness. Modern environmental philosophy states that the Earth is not just a resource, but a living entity. Chhath lives this philosophy in its practice without any scriptures or teachings. This makes it even more relevant than modern ecological thinking.

When Indian expatriate families celebrate Chhath on the riverbanks of London, New York, or Tokyo, they aren't simply performing a tradition—they are imbuing modern globality with their folk consciousness. This is the moment when tradition transcends boundaries and takes on contemporary meaning. In Western society, where the divide between faith and science is deep, Chhath becomes a wonderful medium for connecting the two. This festival demonstrates that modernity and spirituality can be complementary, not contradictory.

In Western aesthetics, the goal of art is to achieve the sublime experience—the moment when a person feels insignificant before something great and infinite. The beauty of Chhath is similar. The thousands of lamps burning simultaneously on the ghats, the water shimmering in the sun's red glow, and folk songs echoing in the silence—all these create a sublime scene where beauty is seen not just with the eyes, but with the soul.

In Chhath, the woman's voice is paramount. She is both the bearer of this tradition and its center. From the perspective of modern feminist discourse, this woman does not worship under duress but, through her own strength and discipline, performs a creative act. Her meditation and her devotion—both are metaphors of her self-reliance. This is the woman who balances the sun with her labor and dedication. While Western women seek self-power in the language of freedom, the Chhath woman finds freedom in restraint. She enters the waters not for anyone else, but for her own balance.

In contemporary times, when the meaning of religion has become narrow, The Chhath festival creates a religion that is not bound by any sect or any mediation. There are no priests, no temples—only humans, the sun, and water. This is a folkloric form of religion, where each person is the worshipper of his or her own spiritual practice. It is closest to the democratic ideal of modern society, where equality, devotion, and beauty coexist.

The greatest miracle of Chhath is that it freezes time within itself. Whether it's a village pond or a city rooftop, the sun rises the same way, the water shimmers the same way. In this stability lies its modernity—a tradition that doesn't fear change, but embraces it.

According to modern philosophy, humanity's greatest tragedy is that it wanders in search of meaning. Chhath offers not a meaning, but an experience—an experience that connects humans to themselves and the universe. The sun's rays fall on water, the water transmits its image to the earth, and the earth transforms its warmth into life. This triangle is a symbol of the cosmic unity that modern science calls the "ecological system" and folk culture calls "Chhath Maiya."

When women, after the final offering, turn toward the sun and join their hands, it is not merely a moment of worship but of self-acceptance. They don't say it, but in their eyes, it means that they are not separate from nature. They are its offspring, flowing in its current. This is the secret of Chhath—a peace amidst modernity that is deeper than science and broader than religion.

Thus, Chhath is the most beautiful poem of the modern age—in which faith meets reason, belief dissolves into discipline, and man recognizes himself in the sunlight. This festival is a bridge between memory and consciousness, body and soul, people and world, connecting man once again to the earth. When the last lamp is lit on the ghat, it is not just an earthen flame—it is the flicker of the inner sun that is reborn in every age, in every human being.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0